Last updated on 13/09/21

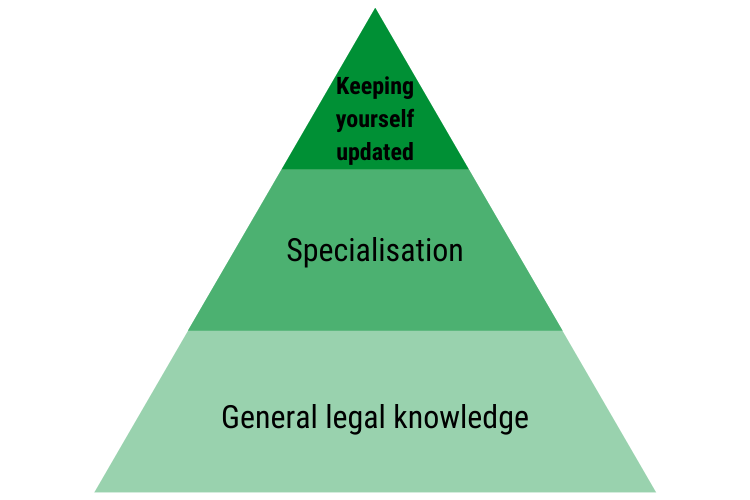

Developing your legal knowledge is an essential element in a legal translator’s career. For me, the process of building up legal knowledge looks like a pyramid made up of three levels, each one helping translators acquire different skills to keep progressing in their career.

Having a good general legal knowledge helps with contextualising documents requiring translation and with developing good legal research skills.

2. Specialisation

Specialising in one or more areas of the law helps with finding a niche, becoming a subject-matter specialist and being more recognisable.

3. Keeping yourself updated

Keeping up with the law is that extra step that helps you stand out as a legal translator and be seen as a trusted professional in your field by potential clients and colleagues alike.

In legal translation nothing is quick and easy. The 3-step process above looks like a lot of work because it is a lot of work. It requires investing time, effort and money. But it pays off. The good thing is that, if you decide to follow this path, there are many ways to do it. You can create your own roadmap and adapt it to your goals, preferences, priorities, finances and personal circumstances.

While acquiring general legal knowledge is something a translator should start working on first, there is no specific level to achieve before specialising. You can keep building your general legal knowledge while you study a specialist subject and continue expanding that knowledge afterwards. And once you have acquired sound subject-matter specialist knowledge, you can come up with a CPD plan to keep yourself updated in that particular area.

Why keeping yourself updated is key to standing out as a legal translator

The higher you go in the pyramid, the less competition you will find. Many translators have a good general legal knowledge, fewer develop a subject-matter specialisation and even fewer keep themselves updated.

A legal translator who regularly engages in CPD courses, events, reading and self-study becomes more knowledgeable, confident, trusted and a better translator overall. Going the extra mile will show regular and potential clients that you are on top of your game.

These are some of the things that keeping yourself updated will allow you to do:

- Spot inaccuracies in legal translation manuals

- Easily discard translations provided by bilingual dictionaries

- Know how a legal concept was previously called or how it is still called, despite recent changes

- Learn about the latest developments in inclusive and plain language

- Better analyse legal news, which are very often misreported in the media

- Spot mistakes in the original text you are translating

- Spot outdated terminology

- Regularly re-assess and fine-tune how you translate certain legal terms

- Feel comfortable attending legal events

- Actively engage in conversations with solicitors and other legal professionals

- Give a good first impression to potential direct clients

As legal translators navigate not only between languages but also between jurisdictions, your legal knowledge development plan should ideally involve as many jurisdictions as you work with. I, for example, (slowly) work simultaneously on three pyramids and keeping up with my field of specialisation (succession law) involves my B language and jurisdictions (England & Wales, and Scotland) and my A language and jurisdiction (Spain (derecho común)).

Keeping up with succession law

The types of documents requiring translation in cross-border succession matters can be very varied, but, for the purposes of illustrating the importance of keeping up with succession law, I am going to focus on wills.

I have worked on numerous wills over the past ten years, and I can assure you that they are far from standardised documents. Wills can vary enormously in terms of format, volume, complexity and language.

Format. Many wills are prepared by solicitors, but sometimes you come across wills handwritten by testators or even template-based wills downloaded from the internet.

Volume and complexity. Generally speaking, the more complex the testator’s estate, the longer and the more complex the will.

Language. Many elements have an effect on the language used in a will, including the specific jurisdiction, who drafted the will, when it was executed and different approaches to plain English and inclusive language.

Lack of punctuation

The practice of omitting punctuation in legal documents is still very much alive in wills. Things are changing and wills executed within the last decade generally include more punctuation than older wills. In any case, punctuation in wills is scarcer than in other legal documents.

Real example: the longest unpunctuated will clause I have come across so far was 26 lines long.

Updating your will after an important life event (getting married or divorced, having children, buying a property) is a practice recommended by solicitors but not always followed by testators. This means that a will requiring translation may have been executed a long time ago.

Real example: in my experience, translating wills executed in the 1990s is reasonably common and I recall translating some 4-5 wills executed in the 1980s (several were even older than me!)

Illegibility

Several factors can make a will requiring translation incredibly difficult and slow to read, such as handwriting, an unusual font, poor scan quality and no line spacing.

Different terminology

Legal terminology is not language-specific but jurisdiction-specific. That is why, ideally, you should try to keep up with the law of your field of specialisation in every jurisdiction you work with. Not only will you be up-to-date with terminology specific to your area of the law but also with more general terms and expressions.

Example: the word ‘outwith’ in an English translation of a Spanish will may raise eyebrows in England and Wales, as it is a Scots term.

A legal translator making a real effort to keep himself or herself up-to-date with succession law will know

- that ‘estate duty’ was replaced by ‘capital transfer tax’, which was replaced by ‘inheritance tax’;

- that ‘testatrix’, while still not uncommon, is being replaced in wills by the inclusive form ‘testator’;

- that a deed of variation is also known as ‘deed of family arrangement’ and that HMRC often refers to it as ‘instrument of variation’;

- that ‘free estate’ means different things in England and Wales, and Scotland;

- that ‘double probate’ does not exist in Scotland; and

- that in a Scottish ‘notarial execution’ of a will a Notary Public has not been required since 1924, despite the term still being widely used.

Mistakes

I come across mistakes in English wills more often than I would like to, mostly in Spanish addresses, but not only. Mistakes cannot be ‘fixed’ in a sworn translation. If there is a mistake in the original will, the mistake will also appear in the translation, followed by [sic], so that the reader knows that it is not a translation mistake, but a literal translation of a mistake in the original.

Alterations

Examples of alterations include interlineations, deletions and marginal additions, together with the authentication (if any) of such alterations as required by the applicable law of the corresponding jurisdiction at the time of executing the will.

Plain and inclusive language

Different legal firms have different approaches to plain and inclusive language. This poses several challenges to translators. The first one is whether or not to maintain the approach taken in the original will, as it may differ from the approach generally taken in the other language and jurisdiction. If the original will uses plain and inclusive language and the translator decides to maintain that approach, the next challenge is how to do that effectively while keeping consistency, accuracy and avoiding ambiguity and other issues.

On top of that, translating wills (and related documents such as codicils and letters of wishes) has a particular and unique disadvantage when compared to translating many other legal documents: the translator cannot contact the testator with questions or ask for clarifications, for obvious reasons.

No external help is available to deal with any issues arising during the translation process. The translator can only rely on the contents of the will. Therefore, acquiring good general legal knowledge, specialising in the field and keeping up with the law is not only advisable but key to producing a quality translation.

DISCLAIMER

The information included in this article is correct at the time of publication/last update. This article is for informational purposes only, does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied upon as such. Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. ICR Translations will not be liable for any loss or damage arising from loss of data or profits as a result of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

Irene Corchado Resmella, a Spanish translator based in Edinburgh. English-Spanish sworn translator appointed by the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Chartered Linguist and member of the CIOL. As a legal translator, I focus on Private Client law, specialising in Wills and Succession across three jurisdictions (England & Wales, Spain, and Scotland). Affiliate member of STEP. ICR Translations is registered with the ICO and has professional indemnity insurance.